How to Spot a First Edition

Two common conversation starters we get: “Do I have a first edition?” and “I have a first edition.” The first one portends work for us and likely disappointment for the customer; the second one often leads to us explaining why the book is not a first edition while trying not to make the customer feel like a total numbnuts.

Luckily there are lots of ways of ascertaining whether or not you have a first edition and this is not the first article written on the subject. You can read more HERE, HERE, and HERE. But we did skim through all of these articles and ours is the only one to use the word “numbnuts.”

As defined by the ABAA (the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America), a first edition is defined as “All the copies printed from the first setting of type; can include multiple printings if all are from the same setting of type.”

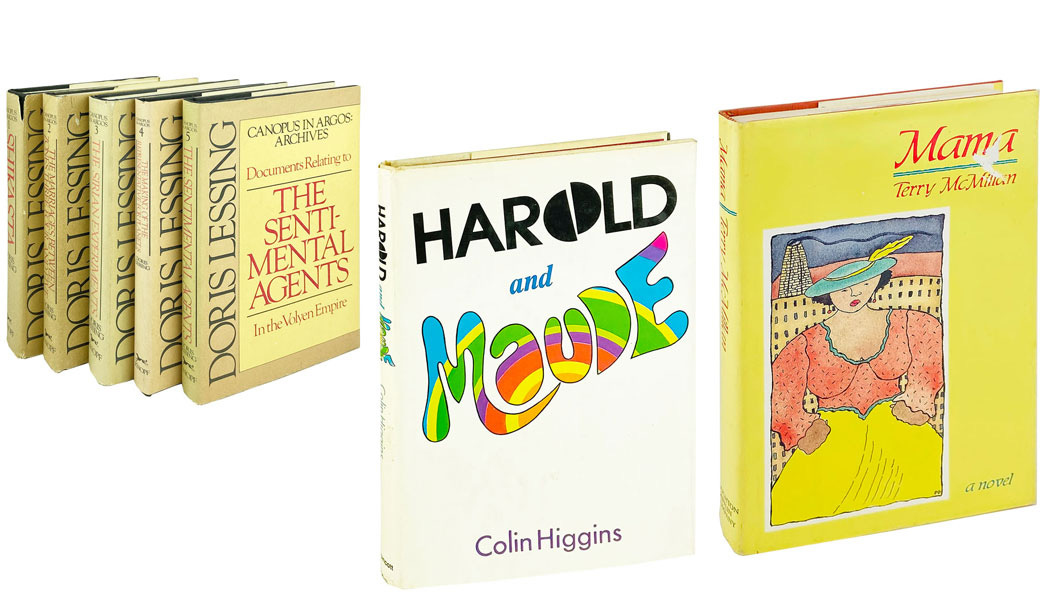

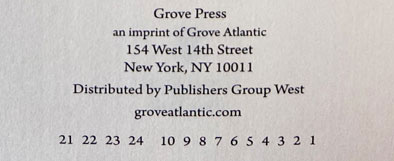

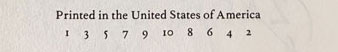

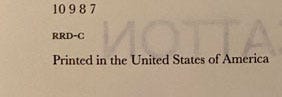

In this article we will be starting in the present and working our way back to 1900, beginning with identifying first editions among “hypermodern” books, generally published from 1970 to the present. Nineteen seventy is a significant date in book publishing—it was the year that the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) was first introduced and it coincides with the growing practice of identifying first printings using the number line on the copyright page, located on the back (i.e. the verso) of the title page. Today, most hardcover books published by the major publishing houses employ this method. Some also include the “First Edition” statement as well, but occasionally fail to remove it with subsequent printings. While the statement in bold above claims that a first edition “can include multiple printings,” it is disingenuous to say that those reprints of a first edition will have the same monetary value as a true First Edition, First Printing. Most professional booksellers will not identify the second printing of a first edition as a first edition at all.

Easy peasy. Except for Random House, which uses a number code that omits the “1” and must include the “First Edition” statement. Dang. Why is streamlining First Edition identification so darn hard?

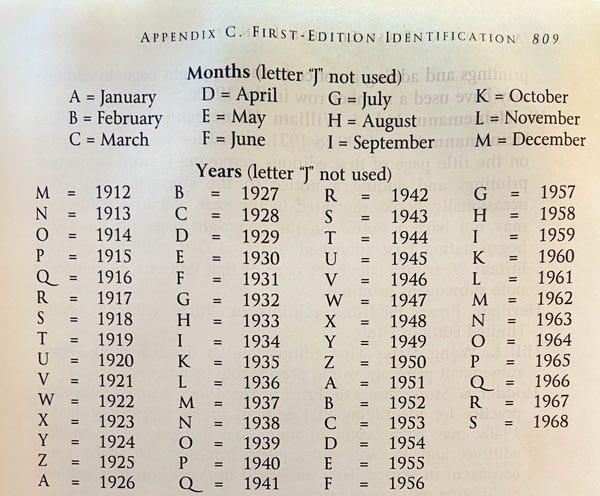

Now that we’ve banged out the last fifty years of first editions in one paragraph and a coupla pictures, let’s go back to the turn of the 20th century and talk about books published between 1900 and 1970, when major American and British publishing houses implemented unique methods for identifying first editions. A lot of these are easy to identify once you know what to look for. Some kindly houses, like Alfred A. Knopf (at least, after the year 1934), explicitly printed “First Edition” or “First American Edition” on the copyright page, noting additional printings as they came up. Others, however, like the nerds at Harper & Brothers, came up with letter codes that indicated the date of publication, assuming you have the key to the code. Your copy of Aldous Huxley’s “The Doors of Perception” has the letter code D-F? That “F” stands for “Fuck, this book is the later, 1956, reprint, not the first, 1954, printing.” (The “D” stands for April, FWIW.) Another sneaky identification practice? A. Appleton’s placement of the printing number (in parentheses) on the final leaf of text. Nobody likes flipping to the back of the book and finding a damn “(2)” hidden in the gutter.

Rather than list every publisher’s first edition identification practices, I highly recommend investing in a copy of Bill McBride’s Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions. It’s small enough to fit in your shirt pocket but not so thick as to stop a bullet.

If you study catalog descriptions written by us or any bookseller specializing in modern first editions, you may also encounter First Edition issue “points” and “states.” These often come up cataloging high points of 19th and 20th century American and British literature, usually because a bibliographer has compared dozens of copies of first printings and pinpointed minor errors that were caught and corrected before a second printing had even gone to press. Unless you have major high spot points memorized, you will need the relevant bibliography to identify the state of your Great Gatsby or Huckleberry Finn. Allen and Patricia Ahearn’s Collected Books is a good, affordable beginner’s guide, though the price guide is now mostly obsolete.

One final word. Yes! You just discovered that you have a First Edition. Congratulations! But do take care. In the world of Modern First Editions, the copy may very well be without value if a) it is missing its dust jacket and/or b) is in bad condition. These make up the Holy Trinity of First Editions Collectors: Edition – Jacket – Condition. Edition – Jacket – Condition. Amen.

The article “Identifying First Editions Pre-1900” will be posted in the coming weeks.

-LNG